.jpg)

Cēsis is Latvia’s thirteenth-largest city, a pretty, slightly rough-around-the-edges place, built, for defensive reasons, on a ridge above the enveloping pine forests and sweeping valleys of the Gauja National Park. Cēsis has changed rather a lot in the last few years, probably more than any other single town in Latvia, and the best place to get the measure of these changes is Lielā Skolas iela, one of the exits to the main square. It’s a little alley barely wide enough for two cars to pass, that runs to the back of the city’s medieval church, which is itself a bit of a microcosm of the city – somehow at once picturesque, imposing and raggedy, its walls are the colour of sandpaper and look rather like a great deal of sandpaper has been taken to them.

Lielā Skolas iela is where I start my morning in Cēsis, interviewing a city council worker in Melnais Gulbis cafe, a cosy, three-table place on the corner, where coffee prices are Riga prices and a rockabilly CD loops endlessly. When I’m done, I stroll a few paces down the road, passing a just-opened health food shop, Ķimene, and find Skola6, a co-working space in a mustard-yellow, rambling former school building. Founder Dita Trapenciere gives me a tour, showing me how people have made the building’s cubby holes and enclaves into their own to make and sell their products; some in particular stick in my mind – a great unattended loom is draped with a half-sketched web of threads; a miniature hairdresser’s is set up in another. Then I write up my impressions right next door in Mala, a low-slung wooden house, its weathered planks a spectrum of black and grey, which hosts a cafe, bar and design shop.

Everywhere I visit is charming and welcoming on the street, but thrown together and slightly dilapitated. At Skola6, the neglected school that once was is still palpable; little has been spruced up or repainted. It has been left relatively unrenovated deliberately, Dita tells me, in order to avoid prospective contributors feeling unwelcome or intimidated. A hand-chalked sign on Mala’s warped wooden door urges visitors to “push harder!” and when I visit it's barely warmer than the street outside – the stove, the only way of heating the space, is in the process of being repaired by a couple of animated chimney-sweeps.

Afterwards, I head down to where Lielā Skolas iela joins the city’s widest thoroughfare, Valmieras iela. It’s there that I find Izsalkušais Jānis, a polished eatery in a revamped fire station. On its serif-shaved website, it describes itself as "an open-type restaurant in Cēsis with an emphasis on local, seasonal products", and the food is indeed excellent, somehow both hearty and light, and requiring quite a few more adjectives and adverbs to describe it than is typical on rural Latvian menus. But this did all come for quite a bit more than I had been hoping to pay on my jaunt to the countryside.

Check Google Street View for Lielā Skola iela, and you won’t find Melnais Gulbis, nor Skola6, nor Mala. On there, it’s just an unremarkable backstreet with a couple of standard beauty salons and supply shops. On Valmieras iela, Izsalkušais Jānis is a staring-eyed, roughed-up derelict. And that’s because Google Street View were here in summer 2012.

.jpg)

Quite a change

The previous autumn I had made my own first visit to Cēsis. In October 2011, I had just recently moved to Riga and was accompanied by a new Latvian friend, a local who had relocated to the capital. She had told me, only semi-jokingly, that Cēsis was the greatest city in the world and that she would move back there as soon as she was able to. She also spent a lot of time light-heartedly deprecating its neighbour, and rival for tourists’ attention, the small town of Sigulda. After the best part of a day in Cēsis, I felt a bit confused by all this.

It wasn’t that it wasn’t a nice place – it was. I liked the crumbling old town, with its undulating, cobbled streets winding unevenly through like a staggering drunk. I liked the towering, sombre church, with its centuries-old graffiti scrawls in the belfry. I liked the expertly-placed lake, backed by castle ruins, filled with gliding swans and looking out onto thick, misty pine forests. There was a mood of cheerful, benign neglect to the whole thing, an appealing sense of “why bother”, but it did seem small – very small – and oppressively quiet.

We went to both of the castles that the small town boasts – one medieval, and preserved only in outline, and the other a 19th-century concoction built alongside its ruins. We went up to its turret and posed for pictures against the forests sweeping off into the horizon; it rained in moody bursts, then the sun sort of came out in a crack of light, spectacular over the firs. Life seemed elsewhere. After that, we went to what I was given to understand was the sole happening place in Cēsis – Cafe Rīga, a convivial place where the buffet seemed inexhaustible and the toilet was done up to resemble a forest glade. Cēsis seemed a place where the scenery had been put roughly in place, but the actors were still practising and the play was yet to begin.

I visited again in the spring, and then not for another three years. During this time, Cēsis was often mentioned to me as one of the cutest or most picturesque or happening or whatever town in Latvia. I didn’t roll my eyes exactly, but again, I did feel a little confused. I also noticed a small but steady trickle of people who I had thought of as eminently urban and sociable either discussing moving to Cēsis or actually going ahead and doing it. Again, strange behaviour, I thought. But my several trips last year convinced me that the town is actually catching up with the perception people had of it.

What has made the difference? Several people I speak to mention Toms Kokins and Evelina Ozola, Latvia’s most prominent urbanists and the impetus behind a number of visible projects in Riga, who relocated to Cēsis from Riga three years ago. A number of festivals and cultural activities have also started up in recent years – in addition to a well-regarded art festival – Cēsu mākslas festivāls, there is LAMPA festival, a several-day celebration of discussion. Many others give credit to mayor Jānis Rozenbergs – elected in 2013, he is one of the youngest city representatives in Latvia, and is perceived as unusually dynamic and imaginative for a Latvian politician; no one I speak to has a bad word to say about him.

.jpg)

The new Cēsnieki

Those who have relocated in the last few years are relatively small in purely numerical terms, but often prominent in their fields, and unusually active and motivated. The vast majority have previously lived in Riga, even if they are not originally from the capital. I canvass a number about why they’ve moved to Cēsis – why here specifically out of all the towns in Latvia? – and I find the same kinds of themes coming repeatedly – “the green heart of Latvia”, “natural”, “genuine”.

It’s not mentioned by anyone I speak to but Cēsis does have a certain power in the Latvian mind, exemplifying a certain kind of Latvian-ness. The Latvian spoken here is reputed to be the purest, the most literary, of any dialect in the nation. At the Battle of Cēsis in 1919, a joint Latvian and Estonian force routed German troops (the Baltische Landwehr) who had intended to halt the two countries’ independence and create a German puppet state under Baltic German administration. It was quite probably the turning point in the struggle for Latvian, and Estonian, thereof, independence. It is generally believed that it was near Cēsis that the blood-red stripes of the Latvian flag were first flown, by a proto-Latvian tribe battling the German crusaders, and it was at Cēsis Castle in 1988 where it was first openly flown again following the illegal Soviet occupation. In one of the jokes that history often plays with ethnicity and identity, the settlement surrounding one of the most powerful castles of the Livonian Order, created to firmly stamp down the barbarous forest-dwelling Baltic tribes, has become among the most ethnically homogenous and coherent in Latvia (Cēsis is 83% ethnically Latvian), a country where most cities are multicultural, and Russian is very often heard in the street more than Latvian.

In a country that often seems to be engaged with multiple crippling identity crises, Cēsis appears confident both of what it currently is and of where it’s going – officially, at least. An indicator as to both of these answers might be found in Radīts Cēsīs (Created in Cēsis), a glossy booklet on all that Cēsis is doing and making right now. Published with assistance from Cēsis City Council and the Latvian Cultural Capital Fund, and edited by Evelina Ozola, it’s designed in a tasteful, restrained style, expensive-looking despite being given away for free, and featuring what seems to be its own special logo on the front, an odd kind of contorted origami pattern. There is parallel text in Latvian and English.

What does this tell us about how Cēsis sees itself, how it wants others to regard it? Well, Cēsis is home-made; Cēsis is well-made; Cēsis is tasteful; Cēsis is quirky – one small clothing company featured concentrates primarily on stamping outfits with deer emblems; Cēsis is outdoorsy – another page highlights cabins in the trees or on stilts; it’s sustainable, again in a quirky way – a feature highlights a local company that offer outdoor pods to charge your phone, powered by solar energy. Cēsis is also strikingly young according to the booklet – it’s a shock half-way through to come across two pages on an elderly woman who weaves elaborate Latvian belts using traditional folk methods. It’s a place where your dreams can be realised, so long as they’re sufficiently small-scale – most of the businesses showcased are run by just one or two people. It’s both cutting-edge and curiously backwards-looking; as one says, with rather questionable historical veracity, “we are not an industrial country; we are a craftsmanship country”.

I talk to Dita from Skola6 about the changes Cēsis has seen lately. She is also a transplant, although one of rather longer standing than most – she moved from the industrial southern Latvian city of Jelgava eleven years ago. Then, she tells me, the town was like “a sleeping beauty” – “there were no interesting cafes, restaurants, no alternative cultural places, etc.” Clearly the last decade has effected quite a transformation. Now she estimates that roughly half, or perhaps slightly more, of those using the spaces available at Skola6 are locals, the rest being recent incomers. One mentions a recent meeting at Mala around twenty strong – when the question was put of whom among them was born in Cēsis, only one person raised their hand.

Gentrification or hipsterisation?

But are these new people who have moved in, most often from Riga, hipsters? It’s an oddly topical question in the country – the word ‘hipster’ was only very recently officially accepted into the Latvian language by the gatekeepers of the tongue, although in a slightly modified version, hipsteris, so that it conforms to the language’s grammatical norms. An article I find from eDruva – a website covering Cēsis and the surrounding Vidzeme region – asks “kas ir hipsteri?” ("what are hipsters?"), and illustrates its answer with a snap of Mala’s weathered wooden door.

The well-made, non-mass-produced, organic, biodegradable products, in the Radīts Cēsīs booklet could easily be characterised and dismissed as simply things that hipsters and other semi-moneyed, broadly irritating subsets of young people with various annoying and expensive accessories like. But this list of adjectives isn’t something bad in and of itself, is it? And Cēsis as it is today, in the right light, in the right type of weather, does seem paradisiacal: a miniaturised settlement stripped of most things that you don’t need, equipped with most that you do, somewhere you can be away from the traffic and bullshit of the city, be a lazy ramble away from genuinely wild countryside, and yet still get a good cup of coffee and go out for a decent, well-made meal once a week, and for much less than you’d pay in Riga. If there are a disproportionate number of cultural events happening while we concern ourselves with all that, who is complaining? However, it’s clear that a number of the city’s residents – quite probably the majority – are off-message, if not actively dissatisfied.

Photo: City Archives of Cēsis

Conflict at the forum

On one of my several recent visits to Cēsis, I went to Cēsu iedzīvotāju forums (Cēsis Residents’ Forum), a Saturday open for all Cēsnieki [people from Cēsis], whether long-standing or recent, to discuss how to move the city forwards. The logo projected onto the screen behind looks wipe-clean and stylish, like it could be promoting a cool new coffee shop or a temporary exhibition at some cutting-edge museum – sharp, pale-shaded lines stretching their way towards and away from letters. I’d estimate around 50 people turn up to this mass problem-solving.

During one of the introductory speeches, concerned with listening but also somewhat self-congratulatory, we are told – “Cēsis ir zīmols” – Cēsis is a brand. The man speaking is animated, with flurries of movements; and a strange hurried patter, which makes people laugh but which I struggle to follow with my makeshift Latvian. When he’s finished, we’re split into three groups and each given an approximate theme which we are to consider over the next few hours.

When we arrive upstairs, we’re divided further, and asked to identify a number of things about the city that we think could be improved. Aside from myself, the vast majority in the group appear in their forties and upwards, and a few are clearly of pensionable age. Shepherding and directing the discussions and conversations, choosing themes, keeping people on point, are a small group of patient, encouraging volunteers in their twenties and thirties. It seems to me at points that they are speaking slightly slower than they usually would, but that may just be me projecting. Initially, at least, those townspeople attending seem patient, biddable – perhaps not surprising, considering they’ve given up their Saturday to improve the city. People readily acquiesce to the initial instructions, and obediently discuss what they are told to.

I can’t contribute much, being a non-resident who has visited a mere handful of times, and I feel a little sorry for Viktors, who is lumped with me as a discussion partner. I do listen and learn, however. The concerns brought up are practical, everyday, mundane: roads, affordability, education – no one mentions culture or the many events that the city puts on. Viktors tells me that he is mostly bothered by the confusing management of traffic on Rīgas iela, one of the main entry points to the city, as well as that there aren’t enough playgrounds for children – well, there are, he says, correcting himself, but they are not sufficiently well advertised by the council. But when I lead him off the set topic and get him to tell me some things about life in Cēsis, he immediately mentions that it is ‘the culture capital’ – although this is just stated as a fact and it’s hard to know if he feels there is much to be proud of in it.

When we have reached our quota of problems, we present them to the group – or, at least, Viktors presents them to the group, and I stand awkwardly alongside – then stick them on the board, and at the end the group votes with a provision of stickers for which we feel are the most pressing. Themes develop: as well as being vaguely dissatisfied with the amenities offered by the city, they are concerned about rising prices and the increasing lack of availability of living space – that Cēsis is becoming unaffordable for its people. One woman, who must be over 80, complains about about the impossibility these days of getting a meal that is simultaneously under five euros and tasty in Cēsis. During the ensuing discussion, Melnais Gulbis, where I had my morning coffee, comes up, and it seems significant of the kind of town Cēsis still is that when one person doesn’t know the still-new cafe, a few participants rush to clarify using the owner’s first name. There are relatively few real back-and-forths – one calls for Rīgas iela, the central route through the Old Town, to be pedestrianised, but another retorts, in fierce tones, that streets die when cars are diverted away.

Some complaints seem directed at problems some way outside the council’s remit: one elderly woman rails angrily for some minutes at the tendency of many people to only clear the snow away from the immediate locality of their driveway or housefront. The audience responds “tā ir Latvijas problēma” (meaning, more or less, that is a general problem everywhere in Latvia). No one mentions culture or the way that the city is marketed – the closest is a sense that it isn’t dynamic enough in winter.

Differences in values – and in motivation

Does this speak of a conflict – or at least a fundamental incompatibility – between the residents born in the city, and those drawn there by its liveliness, creativity, wildness? Lelde Strazdiņa, who runs a pop-up shop below Skola6 and is originally from the town of Saldus, more than a hundred kilometres west, agrees that there are differences, but says she doesn’t see this as a problem at all – the two groups can teach each other – although she does say that “I have only a couple of friends who were born and grew up here”. The main difference she feels, is psychological; the newcomers have a keener appreciation of life in Cēsis, perhaps connected to a broader experience of life, usually being better educated and travelled – ‘[we] appreciate the ‘nature’ that is everywhere in and around Cēsis – clean air, fresh drinking water from a spring (for free!), forest goods at hand’s reach, low prices on the local market for fresh, organic, local produce’. Like others, she sees a gulf in not only taste and outlook, but also levels of motivation between the two groups – ‘where the locals have maybe already seen ten failed attempts, we see possibilities”.

Evija Taurene, who relocated from Riga a couple of years ago, has thought a lot about the differences between the cultural and lifestyle preferences of the two groups: “I think most locals consider themselves very simple, modest and conservative people.” She lists a few examples of how these different tastes are expressed: “When they go out with their family they would much rather choose a place with potatoes and pork chop on the menu, instead of “slowly cooked guinea fowl breast, carrot puree, lingonberry sauce”... when [local] youngsters are searching for something to do, they choose Fonoklubs and a local DJ, not weird hipster music something at Mala.” These people tend to be more dissatisfied with the state of Cēsis, but she says, although “they feel that they deserve something more, but they are mostly not ready to put their own time into improving the city. Or they do not believe in change at all.”

Cēsis does appear to believe in change, however, and has set on achieving it not only through attracting artists and small business owners, but also through large-scale prestige projects, of which probably the most obvious is that concert hall which Evija refers to – the Vidzeme Concert Hall, an impressive, still box-fresh 800-seater venue (into which almost 5% of the town’s population could fit at once), which represents not only a statement of intent and self-esteem, but also a cheeky one-up to nearby, significantly larger Valmiera, traditionally thought of as the capital of Vidzeme Province. Mayor Rozenbergs didn’t initiate the concert hall, but he did strongly support the construction, describing it in a 2013 interview with the Latvian website NRA as “the most significant project in Cēsis in the last 100 years”. Despite being in a relatively small provincial town, it has attracted increasing numbers of concert-goers from the capital itself, many taking advantage of the new Riga-Cēsis/Valmiera express service, which shaves more than half an hour off the usual journey time – another project pushed by Rozenbergs, and one of only two express trains currently in operation in Latvia. Things to attract people from Riga, and means to bring them there.

But it’s worth mentioning that it’s not only locals who have qualms about the way the city is heading. Jānis Ķīnasts is an urbanist and the founder of the placemaking team Nēbetjā. Originally from the city of Liepāja on Latvia’s Baltic coast, he spend eight years in Riga before, together with his wife, a Cēsniece [person from Cēsis], he made the decision to relocate here a couple of years ago, attracted by its peacefulness, unspoilt setting and the promise of “less stupid people around me”. Initially he commuted to Riga every morning, but has now cut down to just one day a week. He stresses that he still loves living in Cēsis and is “a huge believer” in the city, but that he is concerned by some of the longer-term trends.

I’ve been wary of using the “g” word, not wanting to generalise or make people think I’m putting them in a box, but as soon as I start to sound it out, Ķīnasts jumps right in there – telling me “it’s a gentrified city in the making”. He sets out the standard process – a geographically attractive location, “content” brought in from elsewhere. And what are the standard results? “You fuck up the pattern” for the local inhabitants; “they don’t need these fancy Riga-style restaurants”, he says, making reference to Izsalkušais Jānis. If the focus on creative industries are not supplemented by attention to industrial and commercial jobs (here he specifies a number of more unglamorous jobs, harder to put in a glossy magazine – fixing cars, selling construction parts, growing vegetables), he foresees the city declining and its population dipping below 10,000 – at which point, he points out, it’s very hard to recover due to erosion of the tax base. He sees a likely consequence of what is going on in Cēsis as being the growth of nearby, grittier, less pretty Valmiera, which has more extensive infrastructure and a significant industrial base.

.jpg)

A History of Gentrification

Gentrification isn’t a foreign phenomenon in Latvia. Indeed, browsing the internet, I find references to ģentrifikācija going back well over a decade. The emerging, gradual trend for bars and clubs to migrate from the increasingly glossy centre of Riga, over the River Daugava to the rickety but cheap and easily accessible suburb of Āgenskalns is a manifestation of the process visible today. What is definitely the case is that it’s generally been more chaotically handled in Latvia, more ineptly directed, compared to the other Baltic states. If Telliskivi Loomelinnak (Telliskivi Creative City) in Tallinn is the flagship of Estonian gentrification, an industrial site containing a selection of hipster eateries and drinkeries, shops selling handmade products and workshops, which manages to operate as an – admittedly pricy and exclusive – self-sustaining community, Latvia’s most prominent equivalent would be the Andrejsala project, a concentrated attempt a few years ago to enact gentrification-by-attracting-artists focused on a a semi-inhabited, post-industrial peninsula on the outskirts of Riga’s centre.

Today, there are few signs that any of that ever happened. In 2004, it prompted a series of excitable articles from the local press, as it became a creative free-for-all; artists relocated there, tempted by the favourable rates, and quirky enterprises, dirt-cheap hipster bars, art spaces and idiosyncratic hostels started up and won devotees. But the onset of the economic crisis in 2008 hit it hard, and soon after it was earmarked for corporate development and everyone interesting was forced to leave. Today it is gentrified by some definitions, but it does appear to have skipped a few stages in the process – few of the regeneration projects once intended for the district (a contemporary art gallery, most ambitiously) have come off, and now it's a mostly silent, deadened sort of space of anonymous offices and semi-converted factories. Its most significant contribution to the counter-culture in recent years has been the legions of beer-swigging youths who line up, legs swinging, at the distant tip of the peninsula on sunny days, away from all the gentrification, where you can watch the ships go by.

Other local residents express doubts that are more tentative, while still having a basic faith in the project and those manning it. Sanda Salmiņa has lived in Cēsis all her life and says “the only things that cause me concern are whether the city’s image is too much in advance of the real conditions, because we are still lacking effective solutions to practical things like buying or renting living space, waiting lists for kindergartens, the state of the city streets – and a lack of places to work, because not everyone can be self-employed”. But, despite this, she expresses a high degree of confidence that they can be dealt with.

A broader point is: even if Cēsis is a success, can it really serve as an example for the rest of the country? Jānis Ķīnasts refers to Cēsis not only as the cultural capital, but also as the “future urbanism capital” because of the presence of Ozola and Kokins, who have been involved in a number of schemes to make the city more attractive and liveable. But there are questions here too. However attractive, self-sustaining and content Cēsis becomes, it’s dubious whether the experiences of a settlement of barely 15,000 people can really be of much use when considering how to regenerate and redefine very different cities like Jelgava, Liepāja, Daugavpils, the kind of places where most of the population lives, industrial cities several times the size of Cēsis, developed to a large extent under the Soviet Union. This is without mentioning Riga, the biggest city in the Baltic states, which even after 25 years of steady population decline still has at least thirty times more inhabitants than Cēsis.

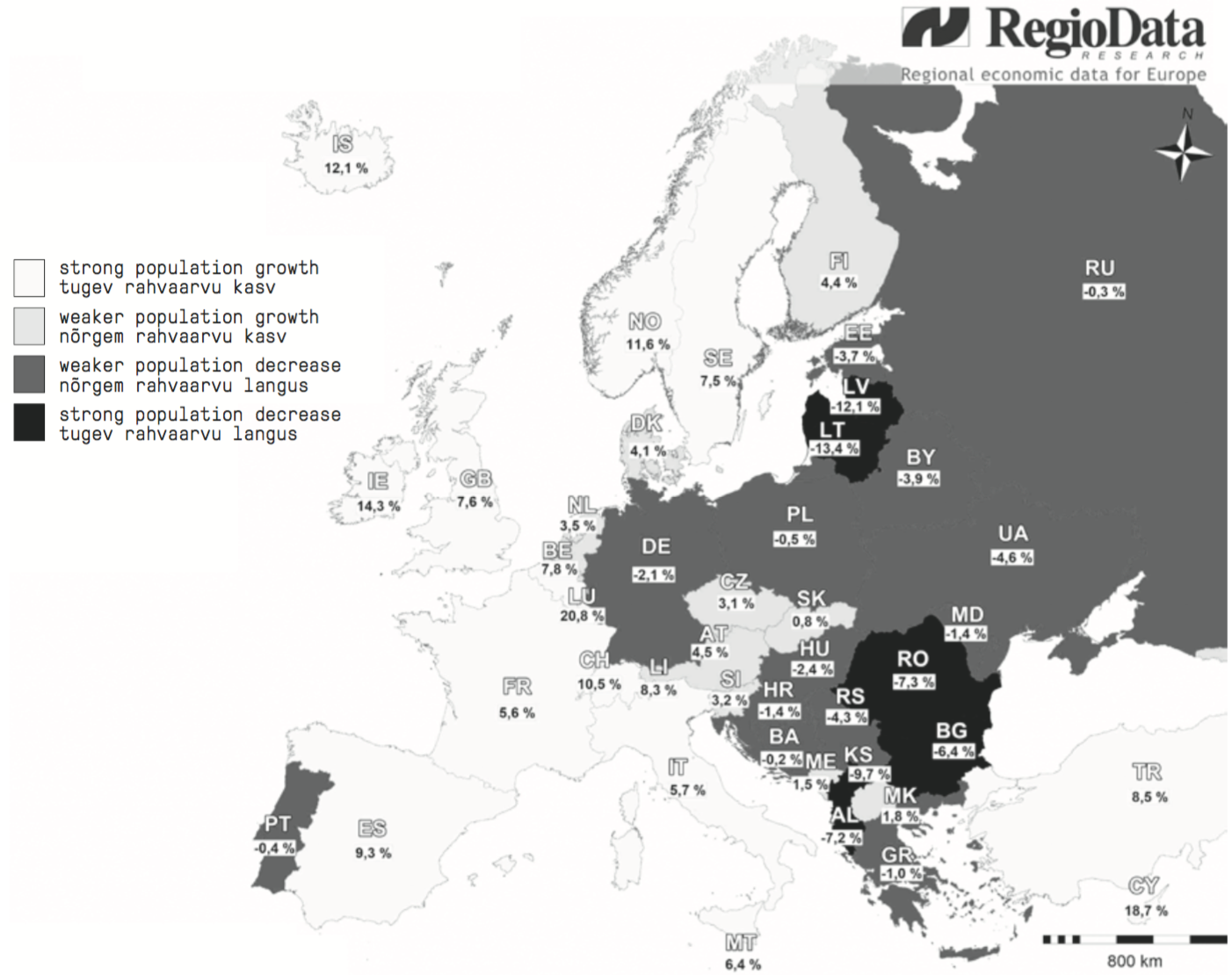

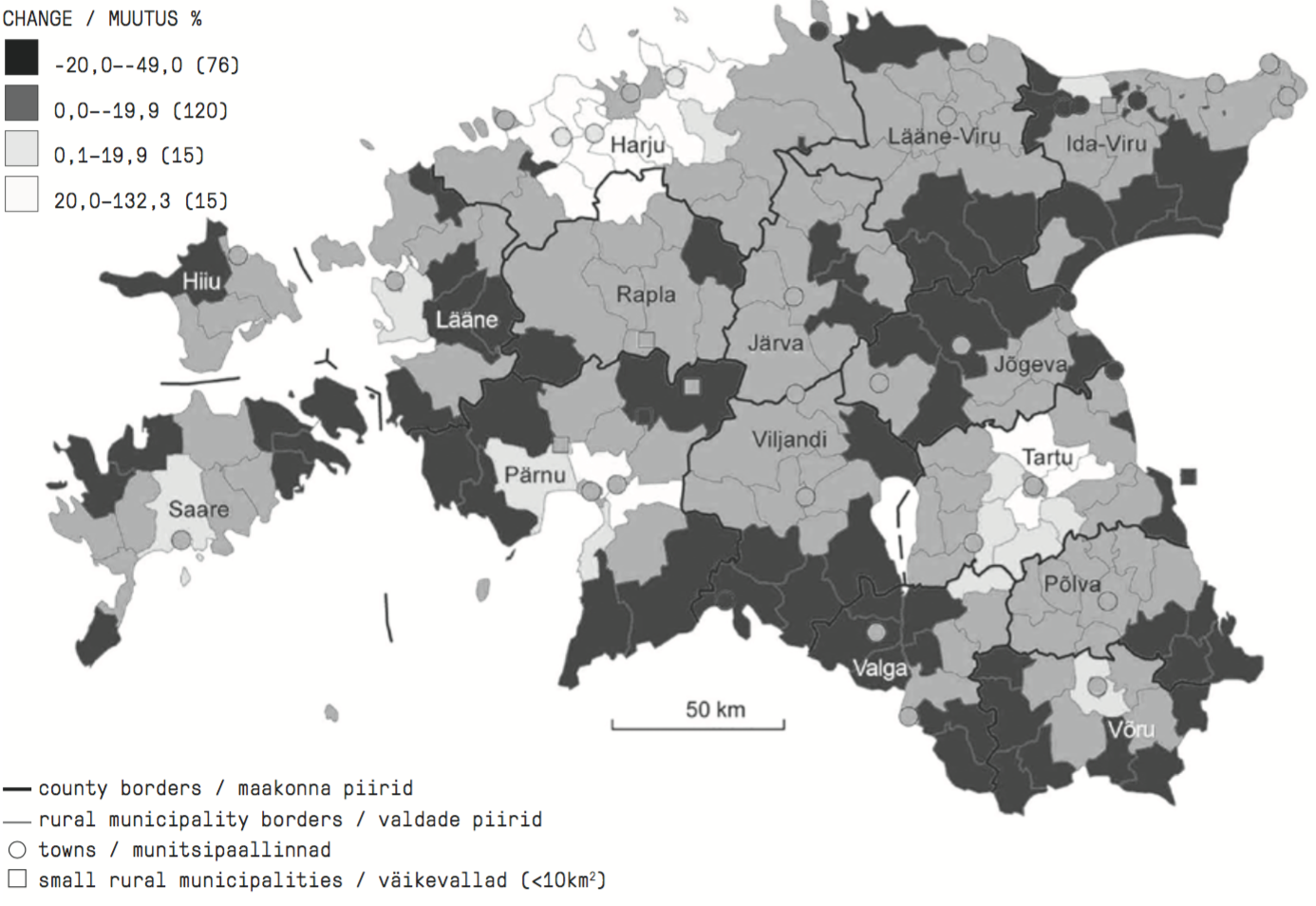

A few days before we speak, I notice that Ķīnasts has retweeted an interesting map, which shows the proportion of the population resident in the capital for each European country. Latvia’s figure, 36.1%, is the highest on the map, ahead even of micro-nations like Liechtenstein and San Marino – and that’s without considering the fact that if you include the towns that ring Riga and the line of seaside towns of Jūrmala, it’s more like half. Riga dominates Latvia in every way, sucking everything towards itself – the unquestioned centre for absolutely anything of importance in Latvia. For this reason, Ķīnasts sees the mere fact that people are moving out of Riga, no matter where they are moving to, as a positive, a way of wearing away at this intimidating, unbalancing statistic. Cēsis City Council has the aim of growing its population by at least 8,000 by the year 2030, although it’s not yet entirely clear where those people will live – a lack of living space is mentioned by many people I speak to – or what they will do.

Whatever the case, there seems no doubt that the broader economic process affecting Latvia is roughly comparable with what is going on all over Europe, the world even. The country seems not so much to be either sliding downwards or reviving, more to be polarising, splitting even more into winners’ and losers’ camps, those that will adapt and those that won’t. The 2008 financial crisis was crushing and traumatic in Latvia as anywhere in the world, slashing its GDP by more than 20% in a single year, and briefly making as many as a quarter of the population unemployed. Latvia’s statistically strong recovery from that devastation within a couple of years has been much vaunted, not least by Christine Lagarde, but how convincing the plaudits are really depends on where you go. Districts of central Riga and Jūrmala feel dynamic and busy, bubbling with new cafes and bars, shops for people with significant disposable income; they are places that people move to rather than think about how to get away from.

But much of the country does not feel like a place in recovery – I’m not really talking here about the larger cities mentioned earlier, despite their many, possible insoluble problems, because their size means they will always retain a residual core of businesses and entertainment centres to keep jobs around and ensure a kind of identity and pride remains. Where things are quietly desperate is in the mid-size regional centres that aren’t quite pretty or close enough to Riga to benefit from the process which is helping Cēsis – places like Alūksne, Rēzekne or Lelde’s hometown Saldus. They are struggling, often depressing places where it’s tricky to find anywhere to eat after dusk, let alone a health food shop or co-working space. The problems Cēsis is facing are real and significant, but many towns in Latvia would sacrifice a lot to be dealing with them.

Will Mawhood is the editor of Deep Baltic.

Editor’s note: THE CAPITAL OF EMPTY SPACES: DEALING WITH THE SHRINKING OF THE GREAT BALTIC CITY. Another long read from Deep Baltic about urban change in Latvia - this time about the shrinking of the capital, Riga, whose population has dropped by nearly a third since the restoration of Latvia's independence. Will Mawhood speaks to those people trying to redefine the city and turn the proliferation of empty spaces into a resource.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)