The article was published in the cultural weekly Sirp on 17 and 24 October 1997.

“The Development of Political Culture in Estonia” is a translated and abridged version of a chapter from M. Lauristin & P. Vihalemm with K. E. Rosengren & L. Weibull (eds), 1997. Return to the Western World: Cultural and Political Perspectives on the Estonian Post-Communist Transformation. Tartu: Tartu University Press.

1. Holmes, I. 1997. Post-Communism: An Introduction. Cambridge & Oxford: Polity Press, p 16. The unexpected results of democratic reforms have caused many disappointments in both direct participants as well as Western observers. The further the reforms in political institutions advance, the clearer it becomes that real democracy depends on the development of political culture.

2. Verba, S. 1965. Comparative Political Culture. In pye, L.W. and Verba, S (ed.) Political Cultural and Political Development. Princeton, NI: Princeton University Press, p 529; Kaplan, G. (1995), Political Culture in Estonia: The Impact of Two Traditions and Political Development. In Tismeanu, V. (ed). Political Culture Culture and Civil Society in Russia and the New States of Eurasia. New York: M. E. Sharpe, pp 230-231.

3. Gibson, I. 1995. The Resilience of Mass Support for Democratic Institutions and Process in the Nascent Russian and Ukranian Democracies. In Tismearu, V. (ed). Political Culture and Civil Society in Russia and the New States of Eurasia. New York: M. E. Sharpe.

4. Dahl, R. A. 1989. Democracy and Its Crisis. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p 262.

5. Bunce V. 1992. Rising Above the Past: The Struggle for Literal Democracy in Eastern Europe. In Ramet, S. P. (ed.), Adaption and Transformation in Communist and Post-Communist Systems. Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford: Westview Press, p 244.

6. Inglehart, R. 1988. The Renaissance of Political Culture. American Political Science Review, 82 (4), pp1209-1230, p 1220.

7. Cf. Almond, S. A. 1990. A Discipline Divided: Schools and Sects in Political Science. Newbury Park, London & New Delhi: Sage; Gray, J. 1990. Totalitarianism, Reform, and Civil Society. In Paul, E.F. (ed) Totalitarianism at the Crossroads. New Brunswick NJ & London: Transaction Books; Bunce V. 1992. Rising Above the Past: The Struggle for Literal Democracy in Eastern Europe. In Ramet, S. P. (ed.), Adaption and Transformation in Communist and Post-Communist Systems. Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford: Westview Press; Karklins, R. 1994. Explaining Regime Change in the Soviet Union. Europe-Asia Studies, 46 (1), pp 29-45; Holmes, I. 1997. Post-Communism: An Introduction. Cambridge & Oxford: Polity Press.

8. Cf Fleron, F. J. Jr. 1996. Post-Soviet Political Culture in Russia: An Assessment of Recent Empirical Inverstigations. Europe-Asia Studies, 48 (2), pp 225-260.

9. Karklins, R. 1994. Explaining Regime Change in the Soviet Union. Europe-Asia Studies, 46 (1), pp 29-45: 40..

10. See 11. vt. Fleron, F. J. Jr. 1996. Post-Soviet Political Culture in Russia: An Assessment of Recent Empirical Inverstigations. Europe-Asia Studies, 48 (2), pp 225-26, 237-38.

11. Lagerspetz, M. 1996. Constructing Post-Communism: A Study in the Estonian Social Problems Discourse. Annales Universitatis Turkuensis, B-214, Humaniora Turku: Turun Yliopisto, p 131.

The totalitarian Soviet system destroyed democratic political culture and paralysed the society’s ability to evolve independently. This was a much greater success than the attempt to destroy national culture. According to Western analysts, the democratic development has not proceeded as quickly and successfully in post-Soviet countries as desired exactly because the legacy of totalitarianism is still profoundly influencing their political culture and paralyses their ability to create a new system.1

WHAT IS POLITICAL CULTURE?

Politics as a field can be divided into political structure, which comprises subjects that execute politics and institutions of political power, and political culture, which encompasses the intellectual and behavioural aspects of politics.

The components of political culture are:

1) values, norms, beliefs, knowledge and the rules, procedures, traditions and rituals that rely on them. They are valid not only for the events that occur outside oneself but also for the political self-identification of a decision maker, an important part of which is national identity2;

2) the language of politics, concepts and symbols that are connected to political activity, political discourse;

3) political behaviour, practical choices of words, people and activities.

POLITICAL CULTURE IN A DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY

When we evaluate the political culture of a population, we take as one of the main criteria the level of democratisation of the country. Democratic political culture is characterised by the following features3:

1) diversity of political subjects and ideas, political pluralism;

2) tolerance towards other people, communities, ideas and developments, including a willingness to allow conflicting interests and opinions to be aired without opposition;

3) readiness and ability of the majority of people to participate in political life;

4) ability to understand what is going on in politics, comprehend the content of political - choices and decisions;

5) belief in the legitimacy of political institutions;

6) firm rules and customs in the relations between political actors, e.g. a belief in the possibility and desirability of political cooperation mixed with a belief in the legitimacy of conflict4;

7) political and interpersonal trust.

A general precondition for the development of a democratic political culture is an institutional structure that permits a widening of democracy: the society is dominated by power and role relations, rules of making decisions, the way of governing must encourage engagement, tolerance and honest competition, and also allow for the voice of those in a minority or weaker position to be heard.

One can distinguish four main lines of change in the development from Soviet totalitarianism towards liberal democracy: extensive civil liberties in law and practice, representative government, the rule of law, and Weberian bureaucracy subject to control by elected officials.5 The more developed and the more stable a given society is, the more one needs democratic political culture to make economic and political institutions function normally. It is also necessary to have a certain level of economic well-being, although as the best known researcher of postindustrial values Roman Inglehart has noted, ‘economic development does not automatically bring about democracy, and is itself influenced by cultural variables’6.

ATTRIBUTES OF SOVIET POLITICAL CULTURE

The attributes of the Soviet system that have been brought out include totalitarianism, imperialism, Byzantinism.7

Totalitarianism includes the following attributes: the total and monopolistic power of the Communist Party, including the aim to achieve a monopoly on truth, communication and organisation; the nomenklatura as a new ruling class; total control, the suppression of civil society; standardisation and hierarchy of public life; repression of those who stray from the official line of thinking and behaviour.

Imperialism means the attempt to maintain and increase influence in the world and colonialists bids to subdue non-Russian republics and socialist satellite states.

Ideologisation means the dependence of political behaviour and political institutions on the official Marxist-Leninist interpretation of the world and history and the use of science and art as an ideological and propaganda tool.

Byzantinism indicates the important role of the hierarchy of semi-feudal personal relations and dependencies: unlike in rule of law, people depend on the regulations set by people instead of laws. The laws are not working, including the constitution. This is greatly influenced by the centuries-long orthodox tradition of the Czarist state. The state is closed to the West. Soviet political culture can be characterised by the following attributes8:

1) mythical and ritual behaviour which is not based on rational argumentation and logical discourse;

2) use of ideals, positive normativism;

3) messianism, a vision of saving all oppressed people of the world, a vision of the - historically progressive nature of the Soviet system9;

4) closed nature and no tolerance for other ideas and values;

5) the separation of official and unofficial opinions, evaluations and behaviour, and Orwellian double-think and double-behaviour, characterising especially the non- Russian parts of the USSR. Dual personality, however, was widespread even in Russian cities and especially among educated people10;

6) supreme providence, paternalism, being directed from above.

In Estonia, the Soviet doctrine never reached the position of ideological hegemony: Mikko Lagerspetz, who has studied the effect of Communist ideology on Estonian society, claims that ‘there was no hegemonic ideology in the Gramscian sense’11. Double-think and double-behaviour was widespread because of the occupation, and because of the strong ties to pre-World War II society and to the Western world at large.

There was very little hope for an end to the Soviet system; thus, instead of fighting it, people tried to use it for personal gain and to preserve national culture. The more the stagnation of 1970-1980 developed, the more Estonian political culture was characterised on one hand by a pragmatic and cynical use of official structures and ideology, and on the other hand by a desire to get rid of it.

THREE STAGES OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL CULTURE IN POST-COMMUNIST SOCIETIES

In the development of political culture during 1988-1997 in Estonia, and possibly in other post-Communist states, three stages can be distinguished: mythological, ideological and critical-rational.

The mythological stage prevailed during the period of 1988 to 1990, and it was characterised by mass movements and the gathering of people around certain shared goals. Emotional devotion, rather than rational deliberation, made it possible for one million people to counter one of the Great Powers of the world. The characteristic forms of political activity during this period were mass gatherings and rallies, boycotts, sit-ins, and the collection of signatures. Under the guidance of charismatic leaders, rituals of common behaviour emerged, which allowed emotional involvement by the masses. Great crowds of people were united by a common emotional high voltage. Symbols, myths, and rituals triumphed, words had a magical function during large rallies. Speeches, songs and slogans during mass protests were a collective conjuring, a symbolic fight and victory of a small nation over the totalitarian machinery. The same kinds of rituals (holding hands, waving flags, a common rocking to songs or shouts, etc.) could be seen in many then-Communist states in 1988-1989, but also later - for example, during the mass protests of 1996-1997 in Serbia. Political discourse was also ritualistic in its character, arguments were replaced by repetitive exclamations of values and slogans (‘Good and Proud to be Estonian!‘, ‘Freedom‘, ‘One day we will be victorious anyway!‘, ‘The Treaty of Tartu is valid‘). The mythologocal stage reached its zenith in 1988-1989, with the election of the Estonian Congress in 1990 and the creation of new parties, the rationality of political activity increased, an ideological dialogue within the national freedom movement began, the time of unified mass movement was over.

The founder of myth theory Roland Barthes has claimed that myth as a cultural mechanism is often activated in the case of a collective borderline situation when the past is destroyed under the pressure of the unbearable present and rhetorical magic is needed to create a new connection between eras.1212. Barthes, R. 1972. Mythologies. New York: Hill & Wang.

The Baltic peoples had been under the Soviet Empire for over 40 years, and until 1985 there was no sign that this pressure would ever disappear or even decrease. As Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 had shown, no help from the West was to be expected. The West was constantly worried about freedom and human rights in some faraway countries but not the Baltic States that had been left at the mercy of the Byzantine Soviet Empire. The break-up of the Soviet Empire was regarded as a miracle. Both the leaders and the people understood that if the moment was not seized, there would be very little hope for the Estonian people and culture.

The magic of words and rituals was important not only because it encouraged people to work together, but also because the Soviet Empire was built on a mythological foundation. It was based on the mythology of a bright future, and it was customary in official texts to use words having no visible connection to outside reality. In the first stage of the transition, where the new relationships and institutions have not yet taken shape and where there was no variety in political interests, it is likely that democratic values express themselves in the forms used in totalitarian society. Thus, ‘new content’ was poured into ‘old moulds.’

The content of the mythological stage had been the restoration of the state. However, after that had happened, the majority of those who had desired for an independent state did not feel any responsibility for it. There was not enough political experience available, but the lack of time and will were also important factors. Last but not least, the transitional shock emanating from the rapid economic and social changes created serious problems in everyday life.

The Ideological Stage began in 1990 with the creation of new parties and largely continues to this day. In this stage, the values are defined verbally, and the mythological suggestive symbols are replaced by key words characterising political ideologies (e.g. left-wing, right-wing, laissez-faire, social market economy, open society, and a strong middle class). Ideological discourse emerges where different values and political programs are formulated and defended through theoretical concepts, at the same time political activity becomes more professional. Argumentation for a position is more closely connected to the Western ideological narratives than to the political practice of the country.

An ideological, value-rational discourse is dominant in the public debate. Judging ideologies as either ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ is based on certain recognised textual models (‘there is no alternative to right-wing’), political discourse is strongly polarised on the ‘us’ and ‘them’ axis. In elections, support is sought for texts and persons, not for consistent political activity. Low tolerance and the ideological nature of political discourse cause a spiral of silence: people afraid of social isolation do not support non-popular beliefs.1313. See Noelle-Neumann, E. 1993. The Spiral of Silence: Public opinion – Our Social Skin. 2nd edition. Chicago & London: University of Chicago press. First, it concerns right versus left-wing politics, a problem which up to this day is covered with a mythical veil. Only a few want to be ‘lefties’ in their words.

At the same time, many would like to see left-wing political practices and solutions for many social problems, not knowing or not wanting to call it ‘left-wing’ or calling it the ‘true right-wing’.

The people are left out from decision-making, mistrust and the delegitimising of power increases. New political institutions, democratic behaviour and forms of communication took the form of ‘learning’ from the West. In this process of Westernisation, people learned ready-made texts by heart and copied readymade institutions. The political and economic elite learned much faster than the general population, who did not yet feel the representation of their interests and did not understand neither the need, nor the content of Western slogans and procedures. Consequently, the participation activity and interest into politics plummeted. Towards the end of 1992 and in the beginning of 1993, the interest in politics among Estonians was about 50%, compared to the 90% interest during the mythological stage. Now it has risen again to 60-65%. Election turnout, which was 71-87% before gaining independence, has dropped to 51-67%.14, 15 14. Raitviir, T. 1996. Eesti üleminekuperioodi valimiste (1989-1993) võrdlev uurimine. Elections in Estonia During the transition Period: A Comparative Study (1989-1993). Tallinn: Teaduste Akadeemia Kirjastus, p 397.

15. The turnout in the local elections in 2013 was 57% (eds.).

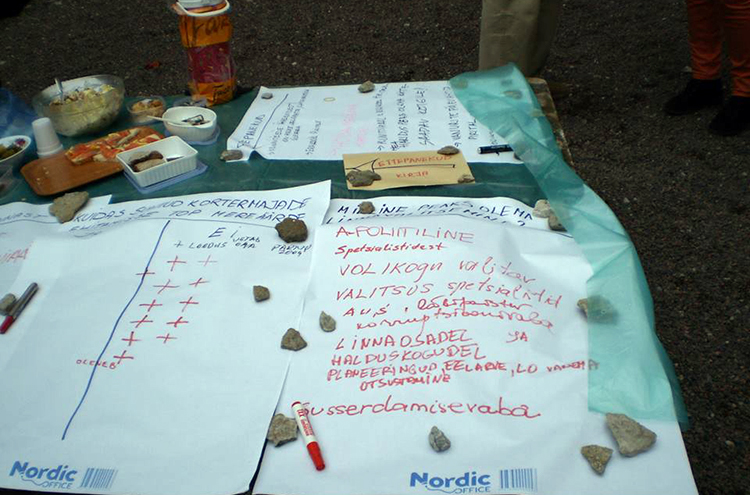

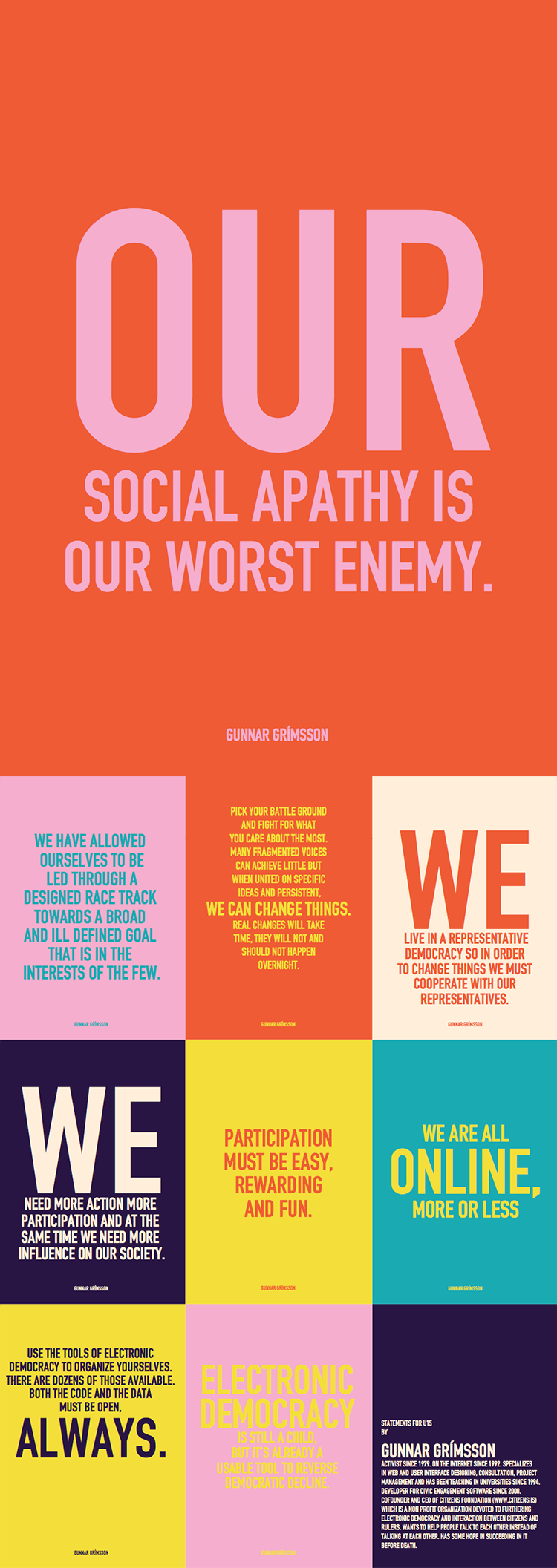

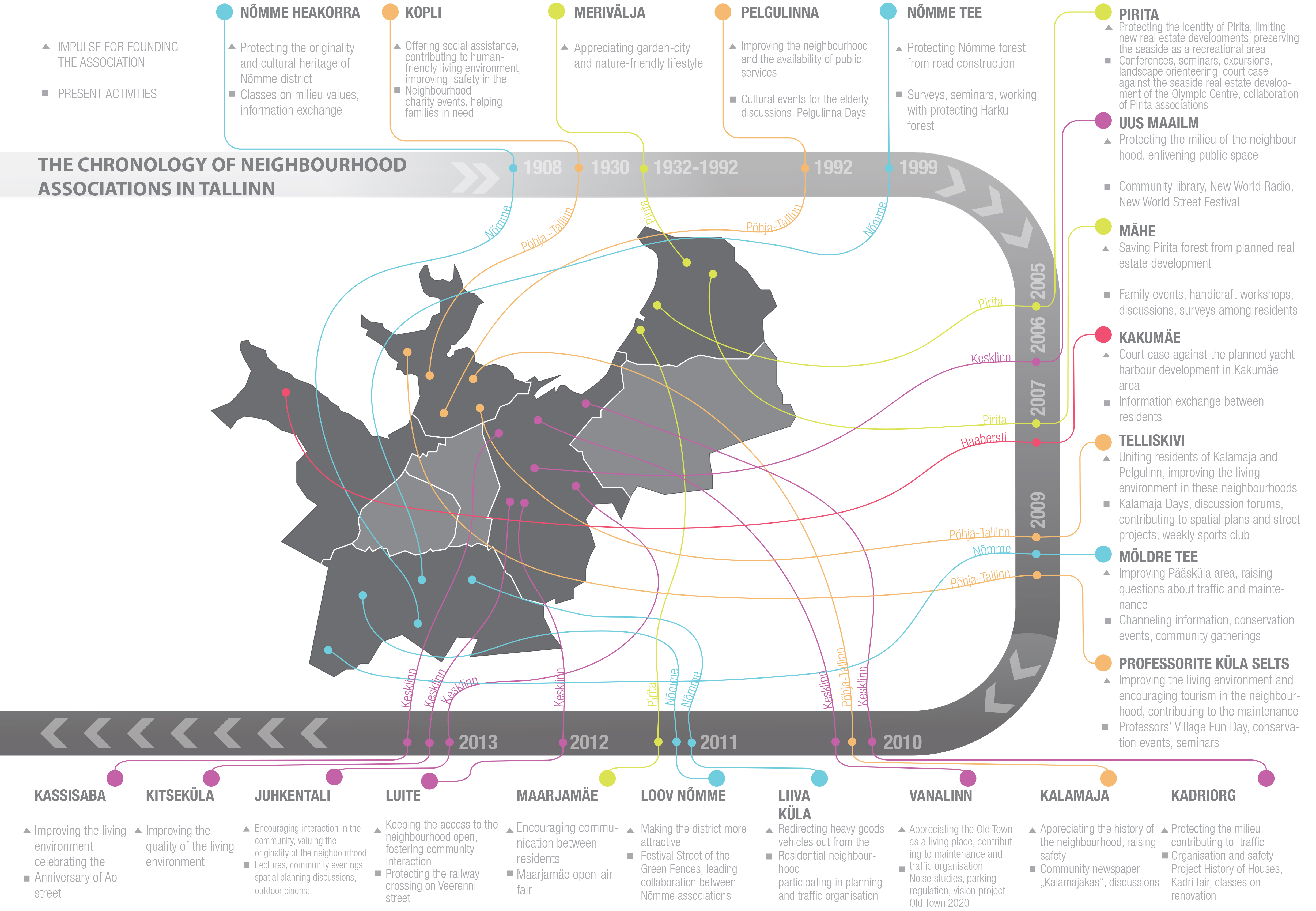

The critical-rational stage will be the stage where true democratic political culture will finally emerge. Firm ties between political discourse and political practice are established. A multitude of opinions emerge. The discourse becomes problem-solving and reflexive in character; different sides are connected by what Habermas calls ‘discourse ethics’, a communicative ethic based on the mutual recognition of the values, transparency and recognition of the parties. Instead of ideologic labelling of opponents, the phrasing of the interests of different sides and debate become important, with the aim of explaining positions and in the case of goals of common interest, the comparison of the means of obtaining them. Both the electorate and politicians know these relations, so that by supporting one political program or another, one may change political practice. This presupposes economic and political stability, and accordingly, a greater freedom in determining directions of development. The increase of general political experience is important, but especially the emergence of new political actors (parties, citizens’ movements, and expert-groups), able to feel, express and defend the interests of the main social groups upon which public policy can be formulated. An agreement thus reached through critical rational public discourse on the common ground of different group interests ensures the stability and understandability of politics.

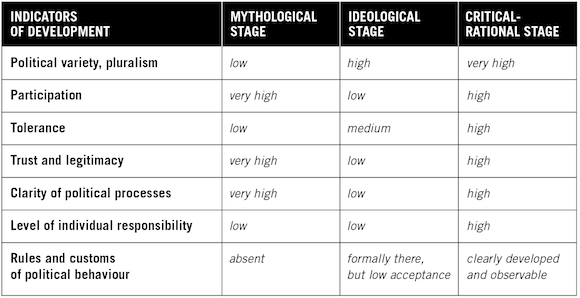

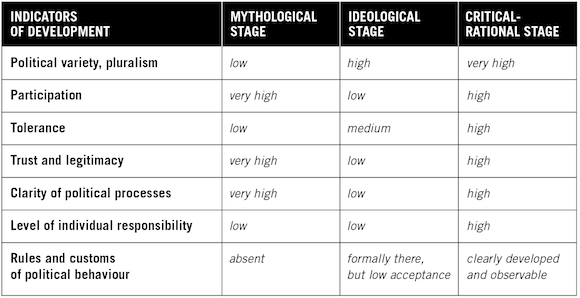

These three stages of the development of political culture are characterised by the relationship of political variety and participation, political variety meaning the availability of choices between different political developments; participation, an active interest in politics. During the mythological stage, participation in political life is at its maximum, and the variety of possibilities is minimal. In the ideological stage, participation goes down, and variety up. In the critical-rational stage, the variety should reach its maximum. We could thus call it a pluralist society, in which the increase of participation occurs through new ‘communication nets,’ not as a mass activity.

Stages of development of the democratic political culture

Our vision of the main characteristics of democratic political culture in the different stages of its development is summarised in table above. As seen in the table, the transition from the mythological stage to the ideological for some indicators is very rapid, and the two stages are contradictory because of the logic of the development of the political culture itself.

This extraordinary situation cannot last for long. It is followed by fragmentation and specialisation, the diffusion of social energy that is accompanied by great emotional disappointments. The ideological phase is characterised by disillusionment, weak or strong anomie, and the inner turmoil which some scholars have called an ‘ideological and moral vacuum’1616. Holmes, I. 1997. Post-Communism: An Introduction. Cambridge & Oxford: Polity Press, pp 18-19..

The development of the critical-rational stage takes years, if not decades. Liberal democracy took shape in Western Europe and North America during a very long process, from the 1820s to the turn of the century. The pace and success of democratisation in post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe depends on whether it is the first wave of democratisation, the first creation of democratic institutions and the first development of democratic political culture (in Russia and other former Soviet Republics, excluding the Baltic states) or recovering from the consequences of the intervening totalitarian setbacks (the post-Communist countries of Central Europe and the Baltic States).

There are two possibilities for further development of Estonian political culture, one more optimistic than the other, depending on the speed with which rational-critical discourse will take over from the ideological stage. True political maturation comes only from the experiences of participants, it demonstrates the connection between political texts and reality. The pessimistic view maintains that the creation of necessary experience will still take a long time, that political knowledge is not growing, and that overall disappointment is increasing and consequently, the ideological stage will continue for years to come.

The practical critique of political texts is part of political maturation. It is a long process, and it does not run smoothly, for it has to digest its own negative experiences. Fortunately, there is still a strong desire to learn in the Estonian population.

PS 16 years later Marju Lauristin commented on the article: '

We were too optimistic – in contemporary Estonia a mix of mythologies and ideological rhetorics continues to dominate. Penetrating that by critical thought is often challenging even for clever people.'

We advise you to analyse the contemporary political landscape in the light of the article with mild irony and open mind and think what could be the reason for this fixation.