Photo: Steven Flusty

Imagine yourself visiting an exhibition at some new museum or other. This should not prove too difficult a task, given the fecundity with which museums have been cropping up in eccentrically angled glass or fluidly excreted titanium across the post-industrialised world. The exhibition itself, likely sponsored by some consortium of corporations anxious to advertise their civic-virtuousness despite their lack of any plausible local or national identity, is regrettably a small one – a collection that consists of a mere four artifacts. These are, after all, times of fiduciary stringency. Nonetheless, the few objects on display (available as authentic replicas in the attached gift shop, at co-sponsoring department stores and first-worldwide by special arrangement with amazon.com) should provide a serviceable impression of ongoing excavations into what might best be called the metapolitan moment.

CULTURED WORLD CITIES

Our first artifact is a small gold-tone and cloisonné lapel pin, circa 1990. It bears the slogan “Building a World City”, surmounted by a handful of stylised cubes forming a skyline in symbolic shorthand. This pin, issued to then-executives of Los Angeles’ Community Redevelopment Agency, celebrated L.A.’s long-sought ascension to “world class city” status through the of-a-piece installation of a high-rise central business district where none had existed a scant fifteen years prior. The skyscraper has become the universally agreed upon icon of world cityhood, a complex concatenation of material culture whereby, if you build them in sufficient density, the world will come. And so they have been built in great numbers, from Los Angeles to Frankfurt to Shanghai, in every city moved to signify indisputably its emergent presence on the world stage. Not that this fetishisation of tower-studded horizons is restricted to the urban apparatchiki, ask any child to draw a city and you will likely receive in return a picture of numerous, grid-bestudded rectangles all standing at tumescent attention. But within the symbolic system of the world city makers, the economystic arcana of location theory, urban entrepreneurialism and A-class office space are empowered by the mudras and mantras performed on stock-exchange floors, and the sigils transmigrated through cyberspace. These are what render the skyscraper not merely an iconic synecdoche inextricable from our collective cultural consciousness, but a powerful ritual instrument of practical magik. Erected and consecrated, it channels capital from on high to transubstantiate the city into a circuit for the electro-ethereal web of plutocratic global "flows". In the process, dispersed cities attain union with one another across vast distances to become a city of cities, a world city system, a metapolis predicated upon a common culture of cash and commodities in-transit – New York and London become NY-LON, ascendant within that supreme trinity of world citydom: New York/London/Tokyo1 1.Sassen, S. 1991.The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

2. Knox, P. and Taylor, P.J. (eds.) 1995. World Cities in a World City System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Taylor. P.J. 2003. World City Network: A Global Urban Analysis. London, New York: Routledge.

3. Hall, P. 1966 (1984). The World Cities. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

4. Friedman, A. 2003. “Build It and They Will Pay: a Primer on Guggenomics.” The Baffler 1/15. pp. 51-56.or, perhaps less archaically, NY-LON-Kong. Beneath this world city of "alpha class" world cities, others take their rightful places in the beta or gamma classes arrayed along a great chain of municipal being determined with recourse to enumerations of each city’s corporate head-offices and producer-service firms.2

While our pin depicts only the architectonic lingam at the heart of this process, the skyscraper requires its attendants if it is to work its worlding magic. In the lay definition, world cities are places where the world’s business is transacted.3 But in their primordial genesis such cities were imperial metropolises, and along with their royal ministries, crown corporations and chartered banking establishments came sites where both the most sublime and grotesque of humanity’s creations, stripped from empire’s hinterlands, could be collected, admired and consumed. Commerce bedecked itself irrevocably in Culture, the banking house and the state house come hand-in-hand with the opera house, and to this day the contemporary world city is without a soul in the absence of the art museum and the concert hall. Without the cultural capital, the intellectual capital at the helm of fiduciary capital will not come. Thus L.A.’s skyline arrived with a complement of two highly celebrated art museums and a completely remodeled third, Frankfurt’s a museum row consisting of more than a dozen fresh-built museums on the banks of the Main, and franchises of Manhattan’s Guggenheim proliferate across the face of the earth.4 It is Culture not just as commodity (an old story, that) but also as bait, pre-packaged events and exhibitions that are shunted, for a fee, from one world city aspirant to another. A condition appropriately isomorphic to the metapolitan harmonisation of settings in which these unitised Culture flows take up their temporary residence – the meltoid metallic curves of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao being all but indistinguishable from those of his Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles.

THE CULTURE OF THE WORLD CITY

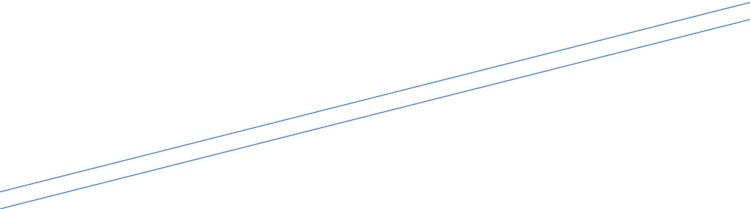

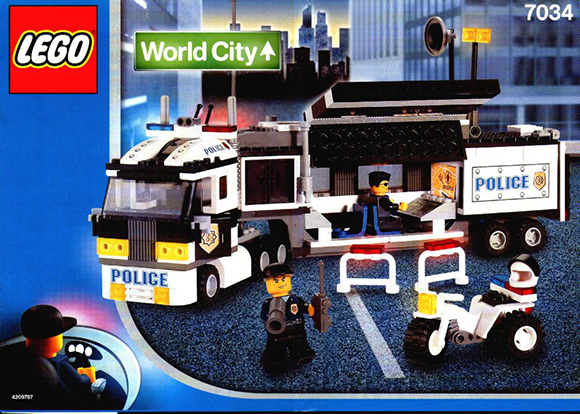

Our second artifact is a boxful of LEGO – multicoloured, snap-together building blocks. This particular boxful is one selected from LEGO’s collection of "World City" building sets that, when assembled according to the photograph on the box, creates a high-tech police surveillance truck accessorised with a three-wheeled motorcycle to apprehend fleeing suspects. The city of the child’s imagination may be a simplified rectilinear skyline, but LEGO’s pedagogy of play elaborates that vision with the detailed specifics of a world city culture – build-it-yourself high-speed passenger and cargo trains on the one hand, and on the other police helicopters, armoured cars and surveillance vehicles; on the one hand mobility, on the other its delimitation and suppression.

These are not oppositions, though, but complements. Machines for moving the possessions and persons of those who have rely upon machines that immobilise the dispossessed. And then some – for every chauffeured town car there are legions of surveillance cameras arrayed along its route, ensuring unmolested passage across the world city and throughout the metapolis, from gated community to corner office suite, from Four Seasons Hotel New York to Four Seasons Hotel London to Four Seasons Hotel Shanghai at Pudong, from Parisian café to Phuket beach resort. Along the way, each stop is an opportunity to acquire new and different tastes, sights, objects and experiences, to sample and edit and recombine them. A vast cosmopolitan hybridity engine, lubed and fueled for perpetual motion with the sacrificial blood, sweat and "ethnic food" of the immobilised – closed out and run over by border walls and the gates of guarded neighbourhoods, held in favelas and gecekondus and refugee encampments, kept in their place as assemblers in Export Production Zones and waiters in Club Meds and janitors in skyscrapers’ washrooms or on trading room floors, fixed in shrunken places where the new is what’s on TV now and the different are those who aren’t quite right a few blocks over thataway. True, upon particularly restive occasions they may elide the walls to irrupt virtually into and across the metapolis. Those walls, however, remain to readily contain virtually irrupting bodies, and contained irruptions are readily extinguished.

The privilege of mobility plugs into cosmopolitanism and tabs together with ever-accelerating hybridisation, while the immobilised slot in with localisms that snap tight with desperation.55. Friedman, J. 1994. Cultural Identity and Global Process. London: Sage; Bauman, Z. 1998. Globalization: The Human Consequences. Cambridge: Polity Press. This is the prescription for connecting the blocks of world city culture, the illustration of a sharply bifurcated complementarity emblazoned on front of the metapolis’ box.

But prescription does not entail subscription, instructions can be disregarded, and the blocks of LEGO’s surveillance truck serve equally well to make a tuktuk, a "technical" bristling with RPGs a’blazing, or a dancing low-rider pickup truck. The building blocks of world city culture are similarly incorrigible – the immobilised prove mobile, privilege cleaves to parochialism, and hybridity is born of desperation. Consider, for example, the executive elite, flying business-class from business-class airport lounge to business-class airport lounge, from business-class hotel to business-class hotel, rarely compelled to speak an alien tongue, ingest an unfamiliar food or negotiate a foreign street. Now, compare with the West African taxi-driver negotiating a fare through the streets of London or Tokyo, a Michoacaña hotel-maid walking a Manhattan picket line, a sailor recruited from Luzon Island to tend the containerised leviathans that ply the shipping routes linking these three cities into one – all obliged to adapt their everyday worlds to that in which they find themselves subsisting, and it to theirs. Now, who among these is the cosmopolitan, and who the blinkered local? True, the circumstances of the refugee compelled across a border differ radically from those of the tourist who crosses by choice, but still, which is doing the real work of hauling other worlds into the world city?

Such are the problematics and potentials of the metapolis, a fluidly demarcated global urban field upon which we all wrestle with the very definitions of alien and native, foreign and domestic, cosmopolitanism and locality. And during such contests we kick up dislocalised localisms, new majorities and emboldened minorities, ever-shifting constellations of popular coalitions, and maybe…just maybe…a chance to reimagine the world city’s fiduciary rationale not as an underlying truth but as just one of many strategic, and inherently cultural, agendas.

WORLDS OF CITY CULTURES

Our third artifact is a tasbih, a set of ninety-nine black wooden beads strung along a tasseled green cord to form an Islamic rosary. This component of the collection was made in Bangkok and acquired in Toronto, but could equally well have been purchased in New York, London, Tokyo, Frankfurt, Hong Kong or Shanghai. We could think of this tasbih as proof of how the world’s ex- (or-neo-, if you prefer) colonial hinterlands penetrate to the global centre, infusing their many worlds into the once-and-neo-imperial world city. But another interpretation is equally valid: in determinations of how the tasbih is (or is not) to be employed for performing dhikr, personal prayer, New York, London and Tokyo are the recipient hinterlands of a very different global centre – a system of world cities comprised of such places as al Madinah, Cairo and Karachi.

Of course, it might be argued that such locales cannot be world cities. They are not centres of corporate command and control, they are woefully undersupplied with skyscrapers, they do not attract armies of immigrant labour, they don’t even have a Guggenheim. In a count of corporate head offices, al Madinah would not even appear as a delta class world city! But for many of those whose patterns of commonplace, symbolically-charged material practices – whose culture – is more beholden to the Qur’an than to the capital markets, al Madinah is central in a very different world city system that relegates New York, London and Tokyo to beta or even gamma class status, at best.

The tasbih is a reminder that while corporate head offices are readily countable, this in no way entails they are all that counts, and counting other cultural indicators yields some very other world cities organised into some very other world city systems indeed. Head offices, after all, are no less cultural artifacts than any other, components of the dynamically patterned practices within which capital and economies are embedded. And if we shift our vision to focus upon the material practices that circulate not conceptions of capital but of, say, divinity, cities we never thought to notice before take pride of place: Vatican City, al Madinah, perhaps Salt Lake City and Dharamsala and, insofar as neoclassical economics presently constitutes the planet’s preeminent theology, Chicago. Nor need we stray so far into the realm of the theological. In a world imbued with cinematic communications, for instance, Mumbai has long stood astride all others for sheer quantity of output while Tokyo, that waning paragon of world cityhood, constitutes a frontier hinterland wherein anime and videogaming fruitfully miscegenate and multiply to infest the Internet and migrate in all directions – here there be monsters, and they’re headed our way!

The metapolis, then, is not simply a world city system but a system of world city systems, and at these systems’ proliferating intersections divergent cities manifest within one another across wide distances – the culture of the arbitrageur embodied by the branch-office of a Manhattan-based bank in Riyadh invariably implies the presence of al Madinah’s priestly culture in any number of masjids dotting the northeastern seaboard of the United States. Such ongoing cultural exchanges generate a landscape of interleaved world cities, one that systematises differently depending upon how one looks, and what one looks for. Further, the disjunctions between these different systematising views are not just an artifact of how we see, but also an impetus to how we act: consider, for instance, the currently escalating tension that indirectly pits the metaphysical logic of al Madinah against the fiduciary logic of NY-LON, tension that manifests at scales ranging from the geopolitical to the city block.

It may well be that being a place where the world’s business is conducted determines world cityhood. The business of the world, however, takes many forms indeed – embedded as it is in wildly divergent patterns of widely differing practices that are simultaneously material and symbolic – and the world city necessarily follows suit. For some time now it has been commonplace to assume the world city as a deculturated economic formation, and to pursue from there such cities’ more-or-less epiphenomenal cultural correlations. Meanwhile, the battle cry against these market-driven urban machines has been: “another world is possible”. A crippling understatement, that, when the polyvalent cultural embeddedness of the metapolitan condition proclaims something simpler yet far more radical: “other worlds are.” Rigorously universally scientifically objective determinations of world cityhood notwithstanding, there are far more kinds of world cities, organised into far more world city systems, than are dreamt of in our geostatistical algorithms.

WORLD CITY CULTIVATORS

Our fourth and final artifact is a hoary platitudinous trope, but no less true for it: mirror. Perhaps ethno-preciously framed in Moroccan tiles, or polychrome Oaxacan stamped tin, its provenance and details are unimportant. What matters is that you view yourself within it, cease to be an exhibition attendee, and become instead a participant.

We are free to depict the global circulation of cultural material, whether instruments of fiduciary capital, exertions of migrant labour, tweets of irruptive dissent, cinematic genres or ritual implements, as flows. But conversely, we can describe them as discrete units comprised of those who send, receive and deploy them, who carry them from place to place and adapt them to new settings. Material practices exist and become meaningful only on account of their practitioners, and that means us. In innumerable and diverse ways, sometimes intentionally but more usually without realising it, we are the world city makers and the sites at which systems of world cities intersect. Whether an executive flying business class between New York and Hong Kong, an immigrant labourer sending remittances back home to the outskirts of Morelia or Accra, or a Muslim doing dhikr in Dearborn, we carry our worlds with us, refit them to the cities in which we find ourselves, and transmute the city as best we can to accommodate our worlds.

The aggregate of our practices is the culture of the world city, its ongoing hybridisations and metapolitan outcomes, and to act accordingly is to recapture just the slightest bit of command and control so long held aloft in those alpha class conurbations of imperial ministries cum head offices. The more of us who do so, the more control we recapture from on high. But failure to do so is acquiescence to a marketist multiculturalism, one in which privilege makes great show of tolerating all comers while zealously insulating itself against them, leaving those so excluded to eye one another with suspicion and fear.

Establishment of common cause amongst the divided and conquered constitutes the best response to such a dog-eat-dog metapolitan dystopia. A shame this seems no mean feat, given how the divisions in question are predicated upon the seemingly irreconcilable divergences of viscerally affective, meaning-laden material practices: kulturkampf or, more specifically, the purported clash of separate and distinct "cultures". Cultures that – despite the planet’s much-touted new penumbra of digitalised para-sociability – seem to (re)constitute themselves ever more exclusively when threatened with the presumptive compulsions of acculturation, Coca-Colonization and McDonaldization.

But while our worlds may remain divergent, in the world city they must also make their homes cheek by jowl, rub up against one another, swap bits and pieces, and propagate the hybrids that result. Interculturation reconciles irreconcilable worlds without sacrificing their irreconcilability. In the streets and the everyday, it mocks both the dictatorship of acculturation and the disingenuousness of multiculturalism, whether in forms as ephemeral as the appearance of soju cocktails in Persian restaurants or as radical as the Zapatista’s anti-authoritarian tactics embodying on the streets of Quebec City or Genoa. In the world city it is everywhere, and it constitutes a small but mighty tool for re-Building a World City from the underside out…especially when fortified with a modest dose of xenophilia.

By xenophilia I do not mean the romanticisation of some Other and the consumption of the othered’s cultural forms, although this at least can constitute a first step – we have become too prone to underestimate the power of breaking bread with others on their own terms. Think instead of xenophilia as a driving thirst to openly engage, and be engaged by, that which is unfamiliar, a sensibility that regards difference as much more than just something that happens and needs to be grudgingly dealt with or, worse, defended against. Xenophilia reminds us of how we too are different, prepares our psyches for deep relations with those who differ from us, and at the same time acts as a remedy to and an inoculation against our mistrust of otherness. So while our lived worlds, and our apprehended knowledge of how the world is, are necessarily too divergent to ever completely integrate, cultivating xenophilia is requisite to appreciating, respecting and even empathetically occupying each other’s ineluctably partial perspectives.66. Haraway, D. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge. Esp. pp. 183-201.

7. Bakhtin, M. (Holquist, M., ed.) 1988. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press. Through xenophilic engagement we develop the capacity to experience a semblance of diverse realities, interact dialogically with others who live those realities, and so negotiate across differential positions7 amiably and with mutual affect. Such dialogical negotiations, in turn, are indispensible if radically diverse social actors are to take a stand against practices whereby power works to silence and disappear many, and order the metapolis as a whole, for the benefit of a few.

So, which shall it be? A place where difference divides, privilege is conserved, and the devil take the hindmost? Or a place where otherness engages, disparity is dismantled, and the production of a metapolitan culture becomes a common, conscious project? We culture the world city, so the choice is ours.

Portions of this essay draw from Flusty, S. 2004.

De-Coca-Colonization: Making the Globe from the Inside Out.

New York, London: outledge.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in

Brenner, N. and Keil, R. 2006. The Global Cities Reader.

New York and London: Routledge.

.jpg)

Steven Flusty, Ph.D., is an intermittent professor of geography and urban design consultant, in which capacities he has visited his own sensibilities upon the unsuspecting cities of three continents.

.jpg)

Photo: suurjalutuskaik.blogspot.com

Photo: suurjalutuskaik.blogspot.com

Photo: Lorna Reed

Photo: Lorna Reed